While Gaskell’s entire characterization of her subject aims to “show what a noble, true, and tender woman Charlotte Brontë really was” (396), meaning middle class and feminine, I will touch on two illustrative instances, dress and love, the knowledge and handling of which attest to Gaskell’s middle-class status as much as Brontë’s. Dress stands out as one of the many seemingly trivial matters that Gaskell highlights in her biography in an effort to help middle-class readers, particularly of course women readers, relate to Charlotte Brontë. Modern feminist scholars are Masters 89 particularly inclined to recognize clothing as a socially meaningful element of Victorian life, and according to Langland, “details of dress, always associated with status, took on increasing subtlety as indicators of class rank within the middle classes. Likewise, dress historian Rachel Worth believes that “the novels of Elizabeth Gaskell are extremely enlightening . . . for their delineation of class as construed through specific styles of dress and specific fabrics

While Gaskell’s entire characterization of her subject aims to “show what a noble, true, and tender woman Charlotte Brontë really was” (396), meaning middle class and feminine, I will touch on two illustrative instances, dress and love, the knowledge and handling of which attest to Gaskell’s middle-class status as much as Brontë’s. Dress stands out as one of the many seemingly trivial matters that Gaskell highlights in her biography in an effort to help middle-class readers, particularly of course women readers, relate to Charlotte Brontë. Modern feminist scholars are Masters 89 particularly inclined to recognize clothing as a socially meaningful element of Victorian life, and according to Langland, “details of dress, always associated with status, took on increasing subtlety as indicators of class rank within the middle classes. Likewise, dress historian Rachel Worth believes that “the novels of Elizabeth Gaskell are extremely enlightening . . . for their delineation of class as construed through specific styles of dress and specific fabrics In The Life, then, clothing presents a possible problem as asign of Brontë’s failure in the realm of middle-class femininity, since, for example, her sister “Emily had taken a fancy to the fashion, ugly and preposterous even during its reign, of gigot sleeves, and persisted in wearing them long after they were ‘gone out.’ Her petticoats, too, had, not a curve or a wave in them, but hung straight and long, clinging to her lank figure” (166). Furthermore, beyond this association with her unfashionable sister, Brontë had apparently failed to clothe her fictional characters appropriately, for in her review, Rigby insinuates that the author must be a man as “no woman attires another in such fancy dresses as Jane’s ladies assume” (111). Through careful maneuvering on Gaskell’s part, however, such alleged ignorance of flattering and socially-appropriate apparel serves as another illustration of how Brontë eventually transcends the disadvantages of her early life. Recurring references to clothing function first as a sign of Brontë’s early social deprivation, then as learning experience, and ultimately as evidence of her “gentle breeding” rather than social ignorance (311). As in many of her fictional works, including Cranford and Wives and Daughters, in The Life, Gaskell reaffirms the importance of dress as a marker of class status and femininity, drawing on the specifically upper middle-class “emphasis . . . on subtle understatement in apparel” rather than ostentatious displays of fashion (Langland 35).

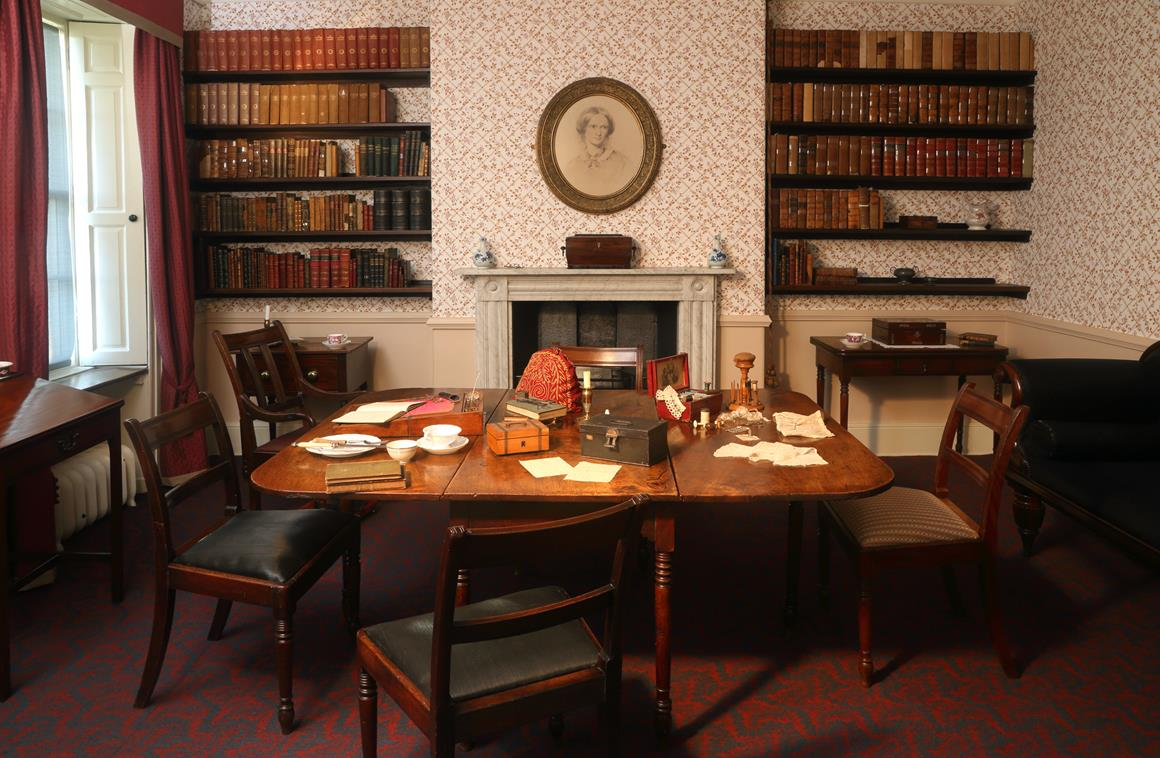

To reach the point where readers see Brontë as simply and elegantly dressed as befitting her middle-class position, Gaskell first has to grapple with the public knowledge that as children the Brontë girls had “strange, odd, insular ideas about dress” (166), as their Belgian schoolfellows noticed when Charlotte and Emily Brontë lived abroad to study French. To account for this social ignorance in terms of fashion, Gaskell locates several contributing factors, including the lack of shops for “dress, or dainties” in Haworth (39), the early death of Mrs. Brontë which left Mr. Brontë to raise daughters (nearly) without female aid, and their spinster Aunt Branwell’s hopelessly out-of-date sense of style.

To reach the point where readers see Brontë as simply and elegantly dressed as befitting her middle-class position, Gaskell first has to grapple with the public knowledge that as children the Brontë girls had “strange, odd, insular ideas about dress” (166), as their Belgian schoolfellows noticed when Charlotte and Emily Brontë lived abroad to study French. To account for this social ignorance in terms of fashion, Gaskell locates several contributing factors, including the lack of shops for “dress, or dainties” in Haworth (39), the early death of Mrs. Brontë which left Mr. Brontë to raise daughters (nearly) without female aid, and their spinster Aunt Branwell’s hopelessly out-of-date sense of style.  Thus, in writing about Brontë as a teenager, Gaskell asks her readers to “think of her as a little, set, antiquated girl, very quiet in manners, and very quaint in dress” (75), though, importantly, through no fault of her own. For one, as an evangelical clergyman, “Mr. Brontë wished to make his children hardy, and indifferent to the pleasures of eating and dress,” and as the knowledgeable Gaskell confirms, “in the latter he succeeded, as far as regarded his daughters” (42). Likewise, Aunt Branwell “on whom the duty of dressing her nieces principally devolved, had never been in society since she left Penzance, eight or nine years before, and the Penzance fashions of that day were still dear to her heart” (75). Noble or kind as their intentions ma have been, neither Mr. Brontë nor Aunt Branwell manage the household with the kind of success Gaskell imagines in her character Mrs. Gibson from Wives and Daughters, who recognizes the importance of selecting appropriate, class-signifying clothing for the young women of a middle-class household.

Thus, in writing about Brontë as a teenager, Gaskell asks her readers to “think of her as a little, set, antiquated girl, very quiet in manners, and very quaint in dress” (75), though, importantly, through no fault of her own. For one, as an evangelical clergyman, “Mr. Brontë wished to make his children hardy, and indifferent to the pleasures of eating and dress,” and as the knowledgeable Gaskell confirms, “in the latter he succeeded, as far as regarded his daughters” (42). Likewise, Aunt Branwell “on whom the duty of dressing her nieces principally devolved, had never been in society since she left Penzance, eight or nine years before, and the Penzance fashions of that day were still dear to her heart” (75). Noble or kind as their intentions ma have been, neither Mr. Brontë nor Aunt Branwell manage the household with the kind of success Gaskell imagines in her character Mrs. Gibson from Wives and Daughters, who recognizes the importance of selecting appropriate, class-signifying clothing for the young women of a middle-class household.

Fortunately, at least in Gaskell’s opinion, Brontë rectified this early disadvantage in terms of clothing once she experienced the wider world and discovered her innate “feminine taste” and “love for modest, dainty, neat attire” (356), which could so appropriately signal her position as a respectable woman of limited means. To show this transformation from “very quaint in dress” to fashion-conscious, Gaskell brilliantly allows Brontë to speak for herself through quotations from personal letters.

In 1851, for example, Brontë wrote to her friend Ellen Nussey, requesting assistance with the purchase of some “lace cloaks, both black and white,” and she spends a full paragraph

enumerating the details involved in this fashion decision (qtd. in Life 356). Of this letter, Miller suggests that it “lets us share an everyday private moment between two female friends, but is also used by Gaskell as proof of Miss Brontë’s ‘feminine taste’ and ‘love for modest, dainty, neat attire,’ moral indicators of her irreproachable womanliness” (67). While Miller correctly assesses how the letter contributes to Gaskell’s feminine picture of Brontë, we should remember that this instance is one of the more positive references to dress in the biography, occurring late in the second volume, and after the publication of Jane Eyre.

The earlier passages in The Life, in which Gaskell deliberately mentions the poor and strange clothing the Brontës wore, make such later references to cloaks, bonnets, gloves, and scarves all the more relevant. In the manner of Gaskell’s fictional heroine Molly Gibson, as the protagonist of The Life, Brontë matures in her sense of style and thus her womanly appeal. In turn, tainted by a penchant for “preposterous” sleeves and petticoats, Emily Brontë, as Jay suggests, is once again “offered up as the scapegoat” (xx), while her more sociable sister Charlotte learns how to present herself properly and in accordance with modern taste. A sign of Brontë’s true success in mastering the art of dressing is the reaction, or rather lack of one, from the ever style-conscious Gaskell upon their first meeting. Although she gossiped freely in her letter to Catherine Winkworth about Brontë’s “undeveloped” body, “altogether plain” face, and unique childhood, Gaskell apparently found nothing to criticize in terms of dress in the “little lady in a black-silk gown” (Letters 123).

Read on: etd.lib.umt.edu/theses/

Read on: etd.lib.umt.edu/theses/

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten